You can’t read hieroglyphics if you don’t understand Egyptian!

Over the Christmas holidays, during the flurry of parcels being delivered to my house, I received a parcel that I had not ordered myself that had been sent to the wrong address. This parcel contained a book; ‘Egyptian Hieroglyphs for Complete Beginners’. Initially I wondered about the type of person that this would be a Christmas present for and whether they had received the book that I had ordered, The Jolly Christmas postman! I secretly hope that they did!

Reading the preface, the purpose of the book is to give you the confidence to read hieroglyphics, so I ended up sitting down over the holiday and seeing what I could learn. I thought that it would be a great opportunity to learn something new, I really enjoy languages and surely this would be like learning to read and write in a secret code! Plus, there wasn’t really very much else to do over the holiday as a result of the restrictions in place.

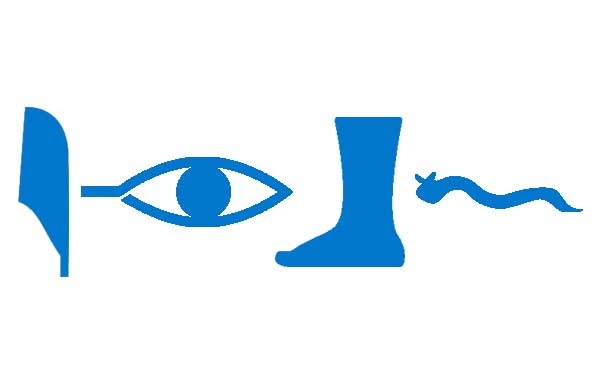

Unfortunately, and probably more obviously to other people, it was not so simple! Learning to read hieroglyphics involves needing to understanding Egyptian language, which I do not. Yes, I could learn that an owl symbol represents the sound ‘m’ and a hand represents the sound ‘d’. I could even start to recognise symbols written together (you can write them left to right, right to left or top to bottom in Egyptian) and could blend or say these sounds together. But I don’t know what the words I am reading mean. Without understanding Egyptian words, I can’t read hieroglyphics and without speaking Egyptian, I can’t write in hieroglyphics.

This instantly put me in the shoes of so many children with speech and language difficulties who struggle to learn to read and write, because of their difficulties understanding and using words. In the same way as when I tried to read hieroglyphics, we can teach a child to listen to and recognise different sounds and then to write the sounds as letters. They may be able to sound out words and say them clearly when reading, but if they don’t understand what words mean, they will be unable to understand anything that they are reading. It is very common for children’s language difficulties to be missed completely, until it is recognised that they are struggling with their reading comprehension.

Educational policy puts very little emphasis on development of oral language skills after Reception Year, which sadly sends a message that it should not be a priority for schools. This is despite the fact that there is a strong evidence base showing that oral language skills underpin the development of literacy skills, and the fact that, if you think about it, we need to use our listening and talking skills so much more in our everyday lives than our literacy skills.

Most tasks, especially after Reception year, involve reading and/or writing, meaning that children with speech and language difficulties are always at a significant disadvantage in accessing learning and constantly being asked to do something that they find extremely difficult. This affects the progress that children with speech and language difficulties are able to make and can mean that they are reluctant to complete these tasks, resulting in challenging behaviour.

The best way to support children with speech and language difficulties in the classroom, is to reduce the focus on reading and writing and spend more time focused on developing speaking and listening skills.

Try and have some tasks during the week that do not rely on only reading and writing, but focus instead on developing listening skills, understanding of spoken language and talking. Consider the aim of your lesson and think about whether it can be achieved by a task focusing on oral language. Although it is still important that children have time to practise their reading and writing skills, does every task need to involve reading and writing to achieve your aims?

You could organise a debate to develop pupils’ ability to structure an argument, or read part of a story as a class and ask the pupils to role play what the characters might do next, then present to the class. You can take photos, record videos or make voice recordings to collect evidence of the outcome of tasks.

A lot of the time in class it is the adults who do most of the talking and children are often told to be quiet. To develop spoken language skills, we need to provide more opportunities for the children to do the talking. Address questions to the class and ask them to discuss their answers in groups, before feeding back to the class. Encourage children to question each other’s ideas by asking ‘Do you agree with that’? or ‘What do you think about that?’ Asking children ‘why’ and ‘how’ questions supports them to extend their thinking using language and develop their problem-solving skills. They will only be able to explain, debate, analyse and reason in their writing, if they can do this successfully when speaking.

It can feel as though by removing the focus of reading and writing from tasks that you are not supporting children to develop these skills. In fact, the opposite is true. The better able children are to understand words when they are spoken and to pull out key information from spoken information, the better they will be able to do this when they are reading. The more practice they have of putting words together to create sentences and expressing themselves using their spoken language, the better able they will be able to do this when writing.

Try putting down the pens and paper to focus on oral language and see the impact on engagement and learning for yourself.